Here are some of the latest filings in the $397 Million lawsuit against the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin, Oneida Seven Generations Corporation & Green by Renewable Energy by Plaintiffs–Appellants in Cook Co. Case No. 2014-L-2768, ACF Leasing, ACF Services & Generation Clean Fuels v. Green Bay Renewable Energy, Oneida Seven Generations Corporation & Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin:

Below are excerpts from the Appeals Brief, using ellipses (“…”) to replace references.

From Pages 4–5:

The relationship between ACF and the Tribe/OSGC began in August of 2012. … On or about August 7, 2012, Kevin Cornelius (OSGC CEO, GBRE President and Tribe member) and Bruce King (CFO of OSGC, GBRE Treasurer and Tribe member) gave a presentation regarding energy projects related to the Tribe at a U.S. Department of Energy conference in Wisconsin. … After the conference, Michael Galich (ACF operations executive) met with William Cornelius (OSGC Board President), Kevin Cornelius (OSGC CEO) and Bruce King (OSGC CFO), who held themselves out as representatives of the Tribe, to discuss energy projects for the Tribe. … Shortly thereafter, Michael Galich met with Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King in Illinois to discuss pursuing a specific plastics-to-energy project (the “Project”) with the Tribe. …

After this first meeting in Illinois, Eric Decator (ACF counsel) drafted a joint venture agreement between OSGC and an ACF entity for the development and operation of the Project with the Tribe. … In or about October 2012, Eric Decator (ACF) and Michael Galich (ACF) participated in numerous weekly telephone calls in Illinois utilizing ACF’s conference call number with Kevin Cornelius (OSGC CEO) and Bruce King (OSGC CFO) to discuss the Project. … On or about October 22, 2012, Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King, who again introduced themselves as representatives of the Tribe/OSGC, met again in Illinois with ACF members regarding the Projects. … At this second meeting in Illinois, Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King advised ACF that the Tribe needed to revise the structure of the initial agreement for political reasons and would utilize an entity known as GBRE to lease the equipment for the Project. … Prior to his meeting, ACF believed the agreement would be with OSGC as GBRE was never mentioned. … ACF agreed to contract with GBRE for the Project given that Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King led ACF to believe that the Tribe/OSGC was utilizing GBRE solely for tax purposes. …

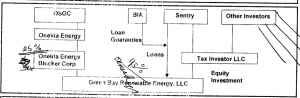

Oneida Eye readers will recall that it was on October 16, 2012, when the Green Bay City Common Council revoked OSGC & GBRE’s Conditional Use Permit to build a municipal solid waste incinerator in Green Bay, which now turns out to have been just days before Bruce King told Plaintiffs-Appellants on October 22, 2012, that “the Tribe needed to revise the structure of the initial agreement for political reasons” to engage in plastics-to-oil incineration with ACF/GCF using Green Bay Renewable Energy, which is owned by Oneida Energy Blocker Corp., which is owned by Oneida Energy Inc., which is owned by Oneida Seven Generations Corporation (which is owned by the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin), as mapped out in the January 17, 2012 Memorandum from Sovereign Finance to the Oneida Business Committee on the subject of ‘ONEIDA ENERGY FINANCING SUMMARY’ which states:

The purpose of this memorandum is to provide the Business Committee of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin with a summary overview of the financial implications of the capital structure proposed by Sentry Financial in their Term Sheet dated January 2, 2012. Bear in mind that these are financial projections and rely upon the assumptions by management and Alliance Construction, therefore actual results could very [sic] materially from what has been presented here. …

…The table on the following page shows anticipated financial returns to OSGC and Sentry based on the capital structure outlined in the Sentry Team Sheet.

The memo to the OBC not only gives detailed ‘Organization Steps’ to develop GBRE, it even contains a organization chart showing the relationships between OSGC, OEI, OEB and GBRE (click image to enlarge):

Oneida Energy Inc.‘s officers as listed in the November 16, 2011 State Energy Program Loan Agreement between the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation & Oneida Energy, Inc. are as follows:

- William Cornelius, Oneida Energy, Inc., President & Chairman

- Mike Metoxen, Oneida Energy, Inc.,Secretary

- Kevin Cornelius, Oneida Energy, Inc.,Chief Executive Officer

- Nathanial King, Oneida Energy, Inc.,Director

Names sound familiar?

Did OSGC and the Tribe make this decision to use GBRE for the plastics incinerator with ACF/GCF in order to be able to justify the $4 Million in conditional loans OSGC had received from the Wisconsin Dept. of Commerce and the WEDC, as well as the $20 Million BIA-guranteed loan that the Oneida Tribe claimed to have secured for OSGC’s & GBRE’s MSW incinerator proposal in the City of Green Bay? How many tens of millions of dollars were the Oneida Business Committee and OSGC planning to put the Oneida Tribe into debt for over these garbage ideas?

The Appellants’ Brief says on Pages 5-6:

On or about October 26, 2012, Equity Asset Finance, LLC (“EAF”) and GBRE entered into a Commitment Letter for EAF to provide financing for the Project. … Pursuant to the Commitments Letter, Bruce King arranged for $50,000 to be wired from OSGC’s bank account to the bank account of EAF on November 6, 2012. … After OSGC wired the initial funds, ACF members, Matt Eden (OSGC’s financial advisor), and Joseph Kavan (OSGC’s counsel) participated in numerous weekly telephone conferences utilizing ACF’s conference call number to negotiate the agreements and to discuss the Project. …

On or about January 31, 2013, Louis Stern (ACF), Michael Galich (ACF), Kevin Cornelius (OSGC) and Bruce King (OSGC) attended a meeting with the Tribe’s Business Committee to give a presentation and to answer questions regarding the Project. … Between January and April of 2013, ACF continued to participate in weekly calls in Illinois with Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King regarding the details and financing of the Project and obtaining a Bureau of Indian Affairs of the United States Department of the Interior (the “BIA”) loan guarantee for the Project, a guarantee only given to an Indian tribe as a borrower. … On March 11, 2013, Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King came to Illinois for a third meeting with ACF to review the approval letter issued by the Wisconsin Bank & Trust related to financing the Project. …

In April 2013, Kevin Cornelius advised Eric Decator that 3 of the OSGC Board members approved the loan commitment letter and that he needed one more Board member’s approval before he could sign it. … Kevin Cornelius repeatedly stated during the negotiations for the Project that he did not do anything without approval of the OSGC Board. … In fact, the elected Secretary of the Tribe [Patty Hoeft] testified that “OSGC would have to approve anything that its entities did” and had control over the approval process of any contract of GBRE. … On or about May 3, 2013, Kevin Cornelius informed ACF that 4 out of 5 OSGC Board members approved the commitment letter. …

Oneida Eye readers will recall that at the May 5, 2013 General Tribal Council Meeting, Oneida Eye’s Publisher made a presentation resulting in GTC voting to approve the following directive:

General Tribal Council directs the Oneida Business Committee to stop Oneida Seven Generations Corporation (OSGC) from building any ‘gasification’ or ‘waste-to-energy’ or ‘plastics recycling’ plant at N7239 Water Circle Place, Oneida, WI or any other location on the Oneida Reservation.

Yet despite the fact that the supreme governing body of the Tribe, General Tribal Council, voted to prohibit OSGC from engaging in gasification on the Oneida reservation, OSGC and their subsidiaries did it anyway, illegally and without the proper zoning ordinances.

See our posts:

From Pages 6-9 of the Brief:

On or about May 6, 2013, Michael Galich held a conference call with Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King to discuss financing, the agreements and the Project. … Around the same time, OSGC’s attorney, Joseph Kavan advised Eric Decator that he needed in-house legal and Board approval before the Master Lease Agreement and the Operations and Maintenance Agreement (collectively, “Agreements”) could be signed. … Louis Stern and Kevin Cornelius signed the Agreements in May and June, 2013. …

From the beginning, the proposed agreements with the Tribe and OSGC contained choice of law and jurisdictional clauses waiving sovereign immunity. … The Master Lease Agreement provides, “THIS AGREEMENT SHALL BE DEEMED TO BE MADE IN ILLINOIS AND SHALL BE GOVERNED AND CONSTRUED IN ACCORDANCE WITH ILLINOIS LAW. LESSEE AND LESSOR AGREE THAT ALL LEGAL ACTIONS SHALL TAKE PLACE IN THE FEDERAL OR STATE COURTS SITUATED IN COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS.” … Similarly, the Operations and Maintenance Agreement provides, “Any disputes pertaining to this Agreement shall be determined exclusively in a court of competent jurisdiction in the County of Cook, State of Illinois.” …

Throughout the negotiations of the Agreements, OSGC and the Tribe representatives repeatedly represented to ACF that they are acting on behalf of the Tribe/OSGC and referred to the Tribe, OSGC and GBRE as though they were one and the same. … Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King repeatedly corresponded with ACF regarding the Project, utilizing OSGC email addresses and OSGC letterhead and utilized OSGC’s office. … Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King represented to ACF that GBRE was only a vehicle for tax purposes, that the Agreements were with the Tribe/OSGC and that Kevin Cornelius had authority to enter into the Agreements and waive sovereign immunity on behalf of the Tribe, OSGC and GBRE. …

In reliance on the representations of Kevin Cornelius, Bruce King, and William Cornelius that they had they permission of the Tribe and OSGC to enter into the Agreements, ACF continuously performed a variety of tasks to meet its obligations under the Agreements once they were executed. … In fact, Kevin Cornelius and Bruce King sent numerous documents related to the Project to Eric Decator in Illinois, but none of these documents referred to GBRE, which was consistent with ACF’s understanding that the actual parties to the Project were OSGC/the Tribe. …

In August 2013, [OSGC CFO] Bruce King advised Eric Decator that OSGC’s Board wanted to review the Project again to determine whether to proceed and sent Eric Decator his slide presentation for the OSGC Board, which included a warning that OSGC “may have additional liability to [ACF] partners in project” if it did not proceed. … On or about August 15, 2013 ACF sent a letter to OSGC’s Board at the request of Bruce King regarding the Project. …On August 30, 2013, Bruce King (CFO of OSGC/Treasurer of GBRE), Kathy Delgado (OSGC Board member), William Cornelius (OSGC Board President), Brandon Stevens (Tribe Business Committee member) and Michael Galich went to ACF’s plant in Bakersfield, California to examine the type of machines that would be utilized in the Project. …Based on all of the foregoing meetings, telephone conferences and visits to ACF’s plant by the Tribe and OSGC, ACF believed it was negotiating the Project with the Tribe and OSGC. …ACF relied upon the representations of the Tribe/OSGC that they were acting on behalf of the Tribe/OSGC. … In December 2013, the General Tribal Council voted to dissolve OSGC.

On March 6, 2014, ACF filed a ten-count Complaint against the Tribe, OSGC and GBRE asserting claims for breach of contract, promissory estoppel, unjust enrichment, tortious interference with contract, and tortious interference with prospective economic advantage. … The Complaint alleges that the Tribe’s vote to dissolve OSGC resulted in the withdrawal of the application of the guarantee to the BIA and commitment to finance the Project which in turn caused the BIA and GBRE to abandon the Project and GBRE to breach the Agreements. …

On May 5, 2014, the Tribe/OSGC filed a Motion to Dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction based on sovereign immunity. … The Tribe, as a sovereign Indian Nation, and OSGC, as a subordinate economic entity created by and for the benefit of the Tribe, claimed sovereign immunity from the Plaintiffs’ suit as a matter of federal common law. … The Tribe and OSGC’s Motion further claimed that there was no waiver of sovereign immunity by contract with “requisite clarity.” …ACF filed its response brief asserting that the Tribe and OSGC were not entitled to sovereign immunity, and alternatively, that the Tribe and OSGC were bound by the forum selection clauses contained in the Agreements and thereby clearly waived sovereign immunity. … On October 7, 2014, the trial court found that there was not dispute sovereign immunity applied to the Tribe and OSGC and further found that there was no knowing waiver of immunity by the Tribe and OSGC. … Based on these findings, the trial court dismissed the suit against the Tribe and OSGC. …

From Page 16:

The Tribe and OSGC have waived sovereign immunity given that: (1) the Agreements contain jurisdictional and choice of law clauses; (2) the Tribe and OSGC are indistinguishable entities; (3) GBRE is nothing more than the alter ego of the Tribe/OSGC such that waiver of immunity should be imputed to the Tribe/OSGC, regardless of any requisite tribal resolution; and (4) Kevin Cornelius had apparent authority to enter into Agreements on behalf of GBRE/OSGC/the Tribe and waive sovereign immunity.

From Page 20-21:

OSGC has unequivocally demonstrated the unity between itself and the Tribe when it declared, “OSGC is controlled by the Oneida Business Committee, on behalf of the Tribe, its sole shareholder.” … In addition, OSGC has declared, “…since the board of directors [of OSGC] is answerable to the Tribe, the decisions…ultimately rest with the Tribe.” …OSGC has further admitted, “[t]he Tribe’s involvement with OSGC, both from a control and operational standpoint is so pervasive. ….” …These declarations regarding the control and unity between OSGC and the Tribe are further bolstered by the testimony in this case.

Patricia Hoeft, elected Secretary of the Tribe’s Business Committee, testified that OSGC was essentially created to make money for the Tribe and was expected to share its profits with the Tribe. … The Tribe provides funds to OSGC to be used for projects and has loaned money to OSGC due to OSGC’s cash flow problem, and OSGC has not paid back those funds to the Tribe. … Further, the Tribe has the power to dissolve OSGC. … All of these facts demonstrate a clear unity between OSGC and the Tribe. Accordingly, any claimed distinction between OSGC and the Tribe should be disregarded as a fiction.

From Page 28–43:

C. GBRE is the alter ego of the Tribe/OSGC

GBRE is merely the alter ego of its parent, the Tribe/OSGC. As GBRE is a Delaware limited liability company, Illinois courts would apply Delaware law in determining whether the entity’s separate existence should be disregarded. … Furthermore, the doctrine of piercing the corporate veil applies to Delaware limited liability companies. … Under Delaware law, a court can pierce the corporate veil of an entity where there is fraud or where a subsidiary is in fact a mere instrumentality or alter ego of its owner. …

“[A]n alter ego analysis must start with an examination of factors which reveal how the corporate operates and the particular defendant’s relationship to that operation. These factors include whether the corporation was adequately capitalized for the corporate undertaking; whether the corporation was solvent; whether dividends were paid, corporate records kept, officers and directors functioned properly, and other corporate formalities were observed; whether the dominant shareholder siphoned corporate funds; and whether, in general, the corporation functioned as a facade for the dominant shareholder.” …

The facts in this case demonstrate that GBRE was the alter ego and mere instrumentality of the Tribe/OSGC. First, the Tribe/OSGC controlled the day-to-day operations of GBRE. Testimony has established that while OSGC is ultimately the owner of GBRE; both the Tribe and and OSGC have the power to dissolve GBRE. … Moreover, “OSGC would have to approve anything that its entities did,” and had control over the approval process of any contract of GBRE. … The negotiations of the Agreements in this case establish OSGC’s pervasive control over GBRE in practice when Kevin Cornelius (OSGC CEO/GBRE President) repeatedly represented that he did not do anything without the approval of the OSGC Board. … Second, GBRE and the Tribe/OSGC operated as a single economic entity when OSGC, not GBRE, wired $50,000 to Equity Asset Finance LLC per the terms of GBRE’s commitment letter. … In addition, the Tribe/OSGC guaranteed loans and extension of credit to GBRE for the Project. …

Lastly, an inference emerges that GBRE is operating as OSGC’s instrumentality where the officers of GBRE and OSGC are wholly identical and where these officers only corresponded with ACF utilizing OSGC email addresses and letterhead and utilized OSGC’s office. … Furthermore, the officers of GBRE/OSGC repeatedly represented, and ACF always understood, that GBRE was merely a vehicle for tax purposes to facilitate the Project. … The facts in this case unequivocally establish that GBRE is the alter ego and merely an instrumentality of OSGC/the Tribe. … As such, the forum and choice of law clauses in the Agreements are enforceable against OSGC and the Tribe. Accordingly, OSGC and the Tribe have waived sovereign immunity and are subject to suit in Illinois and liability under the Agreements. Hence, the dismissal of the Tribe/OSGC should be reversed.

Notwithstanding that GBRE was in effect the alter ego of both the Tribe and OSGC, the evidence absolutely establishes that GBRE was the alter ego of OSGC. … Thus, OSGC is certainly bound by the forum and choice of law clauses, and therefore, has clearly waived sovereign immunity. Accordingly, at a minimum, the dismissal in favor of OSGC should be reversed.

Nonetheless, the Tribe and OSGC were “direct participants” in the wrong alleged in the Complaint, and therefore, should be directly liable. Where a corporation is the sole shareholder of another corporation (as defendant was here), the general rule is that the shareholder-corporation is not liable the conduct of its subsidiary unless the corporate veil can be pierced. …There is, however, a well-established though seldom employed exception to “the general rule that the corporate veil will not be pierced in the absence of large-scale disregard of the separate existence of a subsidiary corporation”; that exception being “direct participant” liability.

“Although not often employed to hold parent corporations liable for the acts of subsidiaries in the absence of other hallmarks of overall integration of the two operations, it has long been acknowledged that parents may be ‘directly’ liable for their subsidiaries’ actions when the ‘alleged wrong can seemingly be traced to the parent through the conduit of its own personnel and management,’ and the parent has interfered with the subsidiary’s operations in a way that surpasses the control exercised by a parent as an incident of ownership.” … It is well settled that “where a holding company directly intervenes in the management of its subsidiaries so as to treat them as mere departments of its own enterprise, it is responsible for the obligations of those subsidiaries incurred or arising during its management. * * * A holding company which assumes to treat the properties of subsidiaries as its own cannot take the benefits of direct management without the burdens.” …

“Direct participation” liability has long been recognized by courts and commentators alike as a basis for holding corporations responsible for meddling in the affairs of their subsidiaries even where the corporate veil remains impenetrable. … This liability, however, is “transaction-specific” and thus limited to those instances where that meddling is directly tied to the resultant harmful or tortious conduct of the subsidiary. … The appellate court in Forsythe discussed four actions which would generally insure that a parent corporation would not be liable for its subsidiaries’ wrongdoing: (1) Maintaining a separate financial unit that should be sufficiently financed so as to carry the normal strains upon it; (2) Separating the day-to-day business of the two units; (3) Maintaining formal barriers between the two management structures; and (4) Not representing the two units as being one unit. …

In Forsythe, the plaintiff asserted that the defendant, despite its legal status as a parent corporation, was directly responsible for the wrongful conduct alleged in the complaint. The evidence showed that the parent corporation’s directors drew up and approved the subsidiary’s budget, boards of both met often simultaneously, the parent mandated the subsidiary’s overall business strategy; and the parent president who was also the CEO of the subsidiary instructed the subsidiary to reduce its budget by 25% which resulted in injury to the plaintiff. The court held that the plaintiff submitted sufficient evidence to survive summary judgment. …

As the parent and subsidiary in Forsythe failed to maintain formal barriers between the two management structures and separate their day-to-day business, the evidence in this case sufficiently demonstrates the Tribe/OSGC’s “direct participation” liability. The Tribe/OSGC controlled the day-to-day operations of GBRE as demonstrated by GBRE’s inability to freely enter into contracts. Specifically, “OSGC would have to approve anything that its entities did,” and had control over the approval process of any contract of GBRE. … The Agreements at issue in this case had to be approved by the OSGC Board, the CEO of which was also the GBRE President. … Further, the Tribe/OSGC wired $50,000 per the terms of GBRE’s commitment letter and guaranteed loans and extensions of credit to GBRE for the Project. …

In addition, the Tribe had the authority to dissolve OSGC, as well as the Tribe/OSGC had the authority to dissolve GBRE. … In fact, the Tribe did dissolve OSGC which caused GBRE to breach the Agreements. The dissolution of OSGC resulted in the guarantee application to the BIA being withdrawn and caused the BIA to abandon the Project. … Clearly, the Tribe and OSGC have failed to maintain formal barriers between the Tribe’s and OSGC’s management and that of GBRE which lead to the Plaintiffs’ damage alleged in the Complaint. …

Moreover, the direct participation between the Tribe/OSGC and GBRE is even more pervasive than in Forsythe when OSGC and GBRE represent themselves as being one unit. … In the matter of Oneida Seven Generations Corporation and Green Bay Renewable Energy LLC v. City of Green Bay,…currently before the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, OSGC and GBRE refer to themselves collectively as “OSGC.” … That case involved the City of Green Bay’s revocation of a conditional use permit to OSGC (or GBRE) for the construction of a waste-to-energy facility. Interestingly, in that matter, as in the instant case, Kevin Cornelius, CEO of OSGC, was the individual who gave a presentation to the Plan Commission on behalf of OSGC and GBRE. …

While there is ample evidence to pierce the corporate veil between the Tribe/OSGC and GBRE, and certainly between OSGC and GBRE, the Tribe/OSGC is at the very least subject to “direct participant” liability for its role in dissolving OSGC, which led to the breach by and the tortious interference of the Agreements with GBRE.

D. The Tribe/OSGC’s waiver of sovereign immunity is effective regardless of any resolution approving such waiver.

The Tribe and OSGC claim that there could be no waiver of severing immunity without a resolution under the Tribe’s Sovereign Immunity Ordinance. Neither the U.S. Supreme Court nor the Illinois courts have addressed the issue. The U.S. Supreme Court has not required anything other than clear unequivocal language for a valid waiver of sovereign immunity. … The U.S. Supreme Court, however, observed that reference to uniform federal law governing immunities by foreign sovereigns appropriate in deciding whether a particular act constitutes the waiver of tribal immunity. … Under federal law, “[w]hen a person has authority to sign an agreement on behalf of a state, it is assumed that the authority extends to a waiver of immunity contained in the agreement. …

In Smith, the court disregarded tribal law requiring a resolution and held that the tribe entered into the contract, which was signed by an authorized agent, and clearly waived sovereign immunity. … Likewise in Bates, the court held that a tribe and its limited liability company waived their sovereign immunity and tribal jurisdiction when the tribe’s CFO had authority to enter into the sale and settlement agreements containing the waivers of immunity. … Similar to Smith and Bates, the lack of a tribal resolution does not invalidate the waiver of sovereign immunity when Kevin Cornelius, CEO of OSGC and President of GBRE, had authority to enter into the Agreements.

E. Cornelius had authority to sign the Agreements on behalf of the Tribe/OSGC and bind the Tribe/OSGC to the waiver of immunity.

The U.S. Supreme Court has observed that reference to uniform federal law governing immunities by foreign sovereigns is appropriate in deciding whether a particular act constitutes the waiver of tribal immunity. … The 7th Circuit also recognized that agency principals are applicable for purposes of sovereign immunity. … There is no Supreme Court or Illinois precedent regarding the enforceability of immunity waivers by tribal agents with apparent authority, and the law among the other states is unsettled. Substantial authority exists, however, to support the proposition that courts should give effect to such waivers. …

In Storevisions, Inc. v. Omaha Tribe of Nebraska,…the Supreme Court of Nebraska applied agency principles to the waiver of tribal immunity and held that the chairman and vice chairman of a tribal council had apparent authority to waive the tribe’s immunity. Similarly in Rush Creek Solutions, Inc. vs. Ute Mountain Ute Tribe,…the court applied agency law and held that the tribe’s CFO had apparent authority to enter into the contract and the waiver contained therein.

Implied authority arises where the facts and circumstances show that the defendant exerted sufficient control over the alleged agent so as to negate that person’s status as an independent entity, at least with respect to third parties. … To prove the existence of apparent authority, the proponent must show: (1) the principal consented to or knowingly acquiesced in the agent’s exercise of authority; (2) based on the actions of the principal and the agent, the third person reasonably concluded that the party was an agent of the principal; and (3) the third person justifiably relied on the agent’s apparent authority to his detriment. …

Kevin Cornelius was an implied agent of the Tribe/OSGC when the Tribe/OSGC exerted sufficient control of GBRE/Cornelius so as to negate GBRE/Cornelius’ status as an independent. …Namely, GBRE/Cornelius could not act without approval of OSGC’s Board, and the Tribe/OSGC guaranteed loans and extended funds and credit to GBRE for the Project. … Nonetheless, Kevin Cornelius was an apparent agent of the Tribe/OSGC based on the Tribe/OSGC’s acquiescence to Kevin Cornelius’ exercise of authority in negotiating and executing the Agreements. … Furthermore, the Tribe/OSGC and Kevin Cornelius made representations from which ACF reasonably concluded that Kevin Cornelius had authority to negotiate the Project, execute the Agreements and waive sovereign immunity on behalf of the Tribe/OSGC. … Clearly, the fact establish that GBRE/Cornelius was an apparent agent of the Tribe and OSGC when negotiating the Agreements for the Project with ACF. Hence, jurisdiction over the Tribe/OSGC is proper based on the activities of their subsidiary, GBRE, and their implied and apparent agents, GBRE/Cornelius.

V. ALTERNATIVELY, OSGC IS NOT ENTITLED TO SOVEREIGN IMMUNITY WHEN IT IS NOT AN ARM OF THE TRIBE.

Notwithstanding, sovereign immunity would not be applicable to OSGC in any event. The United States Supreme Court has never held that corporations merely affiliated with an Indian tribe have sovereign immunity. … Accordingly, the analysis of sovereign immunity of the Supreme Court in Kiowa and Bay Mills, which concerned lawsuits against the tribes and not their corporate affiliates, does not apply to OSGC. …

Although the U.S. Supreme Court has not addressed this issues, it has acknowledged that the United States has taken the position that corporate entities may be arms of the tribe entitled to the tribe’s sovereign immunity. … According to the federal courts of appeals, the proper inquiry is “whether the entity acts as an arm of the tribe so that its activities are properly deemed to be those of the tribe.” ….To determine whether an entity acts as an arm of the tribe so that its activities are properly deemed to be those of the tribe, and consequently entitled to the tribe’s immunity, the Colorado Supreme Court has identified three factors based on the federal courts of appeals: (1) whether the tribe’s created the entities pursuant to tribal law; (2) whether the tribes own and operate the entities; and (3) whether the entities’ immunity protects the tribes’ sovereignty. …The Colorado Supreme Court believed this arm-of-the-tribe analysis was consistent with governing federal law and was not likely to function as a state diminution of tribal sovereign immunity. …

The Courts of Appeals in Wisconsin and New York’s highest court have applied the following similar list of factors to determine whether tribal immunity is conferred on an affiliated corporation:

(1) Whether the corporation is organized under the tribe’s laws or constitution;

(2) Whether the corporation’s purposes are similar to or serve those of the tribal government

(3) Whether the corporation’s governing body is comprised mainly or solely of tribal officials;

(4) Whether the tribe’s governing body has the power to dismiss corporate officers;

(5) Whether the corporate entity generates its own revenue;

(6) Whether a suit against the corporation will affect the tribe’s fiscal resources;

(7) Whether the corporation has the power to bind or obligate the funds of the tribe;

(8) Whether the corporation was established to enhance the health, education, or welfare of tribe members, a function traditionally shouldered by tribal governments/ tribe has legal ownership of property used by organization; and

(9) Whether the corporation is analogous to a tribal governmental agency or instead more like a commercial enterprise instituted for the purpose of generating profits for its private owners/tribal officials exercise control over the administration or accounting activities of the organization. …

The court in Sue/Perior Concrete & Paving, Inc. found that the financial relationship considerations to be the most important factors based on the persuasive consideration of federal percent on the Eleventh Amendment immunity of States. The court recognized that the sovereign immunity of an Indian tribe is not based on the Federal Constitution; however, both types of immunity have an underlying common foundation. … Based on this common foundation, the court found the most significant factor in whether an entity is an “arm” of an Indian tribe was the effect on the tribal treasuries, just as “the vulnerability of the State’s purse is considered ‘the most salient’ factor in determinations of a State’s Eleventh Amendment immunity. … The exercise of complete control over the operations of the affiliated entity by the tribe is not enough to confer immunity. … A corporation is not an “arm” of the tribe if the corporation has no authority to bind or obligate the funds of the tribe. … In other words, protection of a tribal treasury against liability in a corporate charter is strong evidence against the retention of sovereign immunity by the corporation. …

In Sue/Perior Concrete & Paving, Inc., the court found that the purposes of the affiliated entity were to act as a regional economic engine and serve the profit-making interests of the tribe rather than promote tribal welfare on the reservation directly, and such purpose was sufficiently different than the tribe. … The court further found that some of the factors favored the conclusion that the affiliated entity was protected by sovereign immunity, i.e. organization under tribal law, governing body being composed of tribal officials, tribal control over entity’s board of directors and over the administration and accounting activities of the entity. …However, the court determined that the most important factors, specifically those that consider the financial relationship between the tribe and the entity, supported the conclusion that the entity could not benefit from sovereign immunity. …

In Sue/Perior Concrete & Paving, Inc., the record was clear that a suit against the affiliated entity would not impact the tribe’s fiscal resources when the entity lacked the power to bind or obligate the funds of the tribe. The entity’s charter provided that no indebtedness incurred would in any way involve assets of the tribe. The charter further stated the entity would have no power to allow, “any right, lien, encumbrance or interest in or on any assets of the Nation.” …

Likewise here, OSGC lacks sovereign immunity under the arm-of-the-tribe analysis. As in Sue/Perior Concrete & Paving, Inc., the Charter for OSGC specifically provided that “Recovery against the Corporation is limited to the assets of the Corporation. The Oneida Nation [sic] will not be liable and its property or assets will not be expended [f]or the debts or obligations of the Corporation.” … While some factors favor immunity, such as OSGC being organized under tribal law and governed by a board comprised mostly of tribal officials, the most important factors, specifically those that consider the financial relationship between the tribe and the entity, supported the conclusion that OSGC lacks sovereign immunity.

Whether OSGC’s revenues will become part of the Tribe’s resources is inconsequential. … The test, with respect to the financial relationship factors, is not the indirect effects of liability on the Tribe’s income, but rather whether the immediate obligations of OSGC are assumed by the Tribe. … The record establishes that OSGC’s obligations are not clearly assumed by the Tribe. … As such, OSGC lacks sovereign immunity. Accordingly, dismissal of OSGC for lack of subject matter jurisdiction was improper and should be reversed.

CONCLUSION

Neither the Tribe nor OSGC were entitled to sovereign immunity over the tort and equitable claims alleged in Plaintiff’s Complaint concerning off-reservation activities. Even if sovereign immunity were to apply, which it does not, the Tribe and OSGC were bound by the forum and choice of law clauses contained in the Agreements signed by its agent and subsidiary based on their unity and their close relationship to the dispute. Alternatively, OSGC was not entitled to sovereign immunity as it was not an arm of the Tribe. Accordingly, the Order of October 8, 2014 dismissing Defendants, the Tribe and OSGC with prejudice for lack of subject matter should be reversed.

See also regarding Cook Co. Case No. 14L2768:

See also regarding OSGC’s & GBRE’s lawsuit against the City of Green Bay now before the WI Supreme Court (13AP591):

Bonus: